Welcome To All Saints

Whether you are visiting, new to the community, or searching for a church home, you will find All Saints to be an engaging congregation that loves to worship God in the Anglican tradition. We invite you to join us as we meet with our Lord Jesus in Word, Sacrament, and transcendent Worship. (Our rector, Father Isaac Rehberg)

The Anglican Way

Ancient Faith

We hold to the same faith, practice, and doctrine that nourished the earliest Christians.

Transcendent Worship

We worship according to the ancient rhythms and liturgical patterns of the historic Church.

Classical Formation

We form disciples holistically in community through practice of timeless spiritual disciplines.

Join Us As We Worship Our King

Worship Schedule

11122 Link, San Antonio, TX 78213

Sunday

Holy Communion ✝ 9:00 AM

Catechesis Of The Good Shepherd (Kids) ✝ 9:00 AM

Catechesis (Adults) ✝ 10:30 AM

Holy Communion (Choral) ✝ 11:15 AM

Wednesday

Catechesis Of The Good Shepherd (Kids) ✝ 9:15 AM

Matins (Morning Prayer) ✝ 9:30 AM

Evensong (Evening Prayer) ✝ 6:00 PM

The Bishop and Shepherd of our Souls: A Homily for the Second Sunday After Easter

From the 11:15 service on 05/04/2025

Connect With All Saints

Request prayer, provide feedback, or decide on next-steps

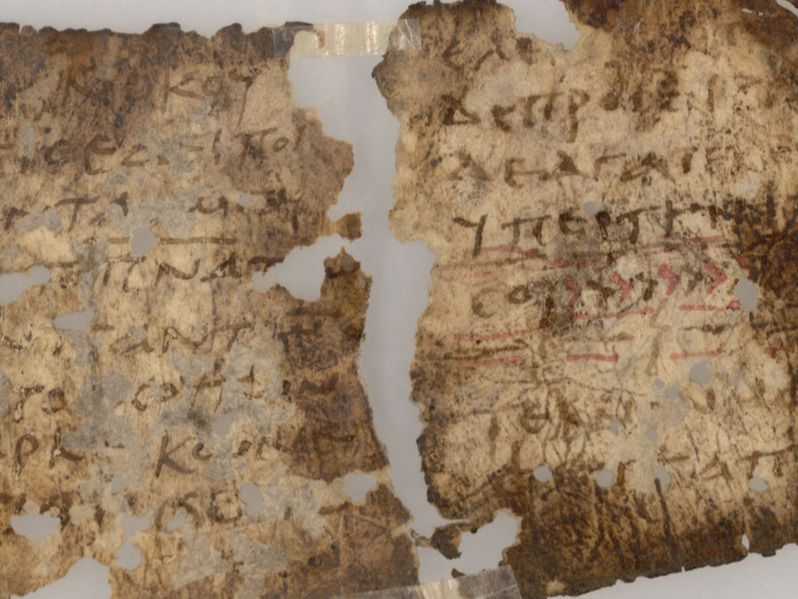

Nicaea I, 235 AD

Part 3 of our Series on the Ecumenical Councils

Christian Education 04/27/2025

The Pure Milk of the Word: A Homily for the 1st Sunday After Easter

From the 11:15 service on 04/27/2025

Family Registration

Add and manage your and/or your family's personal information, check-ins, giving, and more

The Ecumenical Councils (Full Series)

Adult Catechesis (YouTube Playlist)

The Didache: The Teaching Of The Disciples (Full Series)

Adult Catechesis (YouTube Playlist)

Find

Connect

11122 Link

San Antonio, TX 78213

210-975-3234

Explore

Copyright © 2025 | Powered by  churchtrac

churchtrac